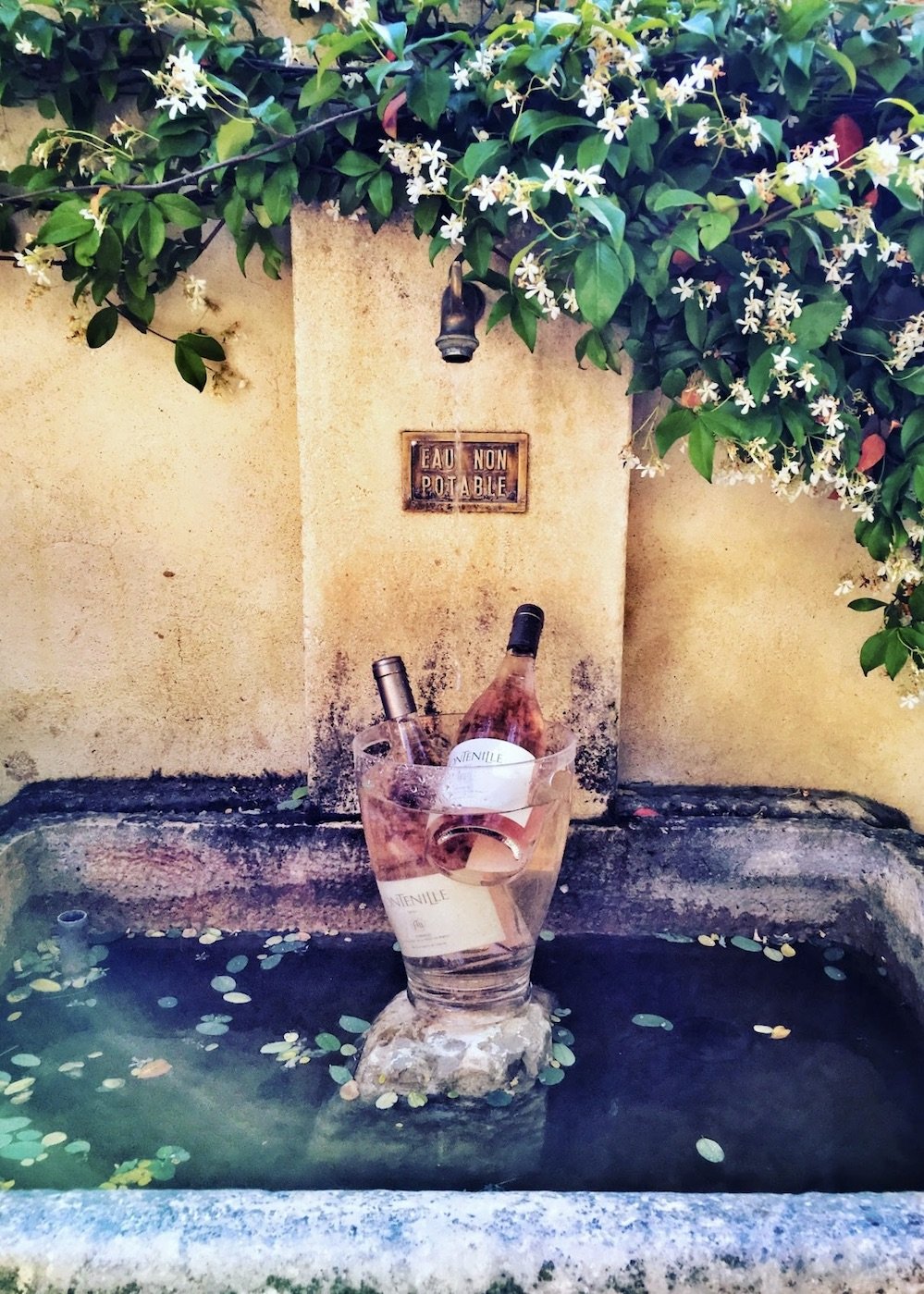

Provence is the undisputed rosé capital of the world. Stroll along the Côte d’Azur and it’s clear that everyone is drinking it. A pale pink bottle of wine sits on every restaurant table and every beach blanket. Brosés (rosé bros) stroll along the shore with bottle in hand, drinking directly from the bottle. Tourists slurp down frosés (frozen rosé).

Rosé seems like a modern wine style, but it’s very old.

In fact, Provence was the first place where the French made wine. And the first French wine was rosé — mostly pink-orange field blends of white and red grapes. Locals were taught wine-making by the Phoenicians more than 2,600 years ago.

In other words, people were drinking rosé on the French Riviera long before people in Bordeaux, Burgundy or Champagne even heard of wine.

Centuries later, the Romans distributed rosé from Provence to the entire Roman world, and Massilia (now called Marseille) was synonymous with delicious rosé throughout the Roman Empire.

That was a big deal back then. Light red wines were far more common than deep reds well into the Middle Ages. (Darker red wines were generally considered inferior to pale reds until just a few centuries ago. Red wine was for commoners and rosé was for the aristocrats.)

What is rosé, anyway?

Red wine is made red with color from the skins of red wine grapes. White wine is white because it’s made from grape juice without skin contact. Rosé is wine made with just a little color from red-grape skins.

This is usually achieved by short skin contact (just a few hours), blending whites and reds (which is illegal in France) or the saignée method, which is the making of rosé as a byproduct of red wine-making. Saignée (pronounced sone-YAY) is a French technique where some juice is removed from red wine during fermentation to increase the skin-to-juice ratio, which intensifies the color and taste of red wine. The removed juice is pink, and fermented separately to make rosé.

The enormous Cotes de Provence AOC alone produces around three-quarters of all the wine in Provence, and roughly 80% of that in the form of rosé.

Most other AOCs in Provence also produce a lot of rosé, mainly using Grenache, Syrah, Cinsault, Mourvedre, Tibouren, Counoise, Carignan, Braquet, Folle Noire and Cabernet Sauvignon grape varieties.

The reputation of rosé was tarnished in the 20th Century with the popularity of two bad Portuguese rosés called Mateus and Lancers, which dominated the US rosé market from the mid 40s to the mid 80s. The super sweet white Zinfandel “blush wine” craze of the 80s didn’t do rosé’s reputation any favors, either. (White Zin was created by accident in 1975 by Bob Trinchero who tried to make dry rosé with the saignée method, and a stuck fermentation foiled his plans. The resulting low-alcohol, high-sugar product turned out to be a hit with consumers.)

But since the 2000s, Americans started discovering better rosé, mostly from Provence. Serious French and American wine snobs started appreciating great rosé only in the last few years.

Now, rosé is made and consumed globally. But the very best is still made in Provence.

And that’s where we come in.

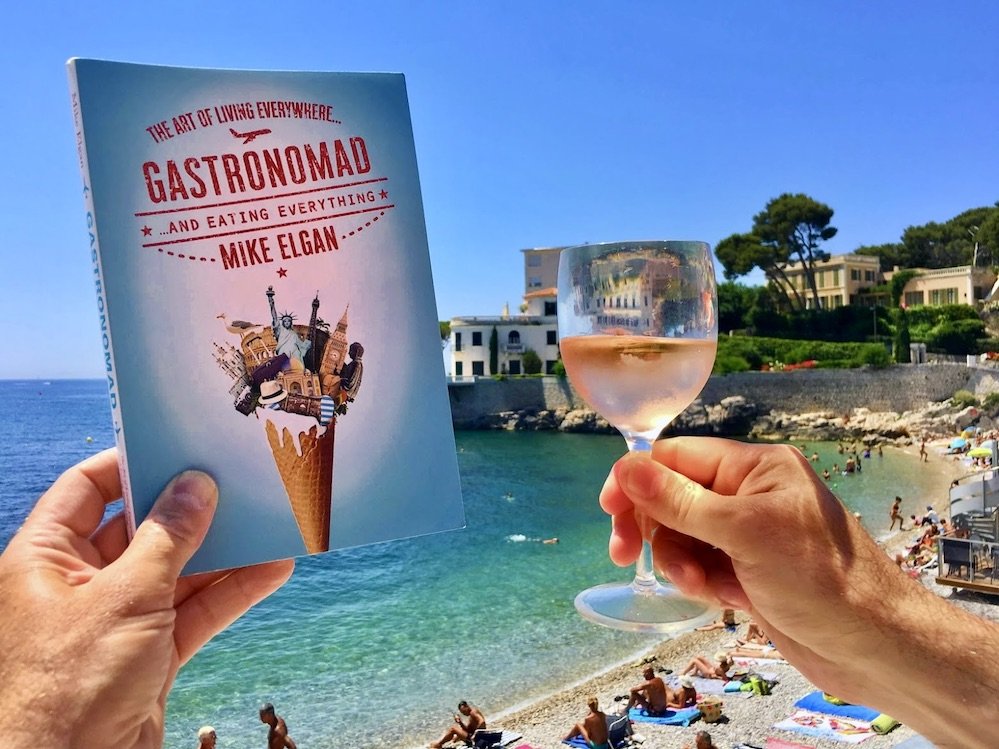

We have searched and researched and tasted rosés all around Provence, and our Provence Experience guests drink only the world’s greatest rosés — wines that are never exported to the US — during our adventure (as well as Provence’s greatest reds and whites).

And we prove once and for all that Julia Child was right: Rosé pairs with everything.

Join us and see for yourself! — Mike