Mexican food and culture is slowly making its way into the collective European consciousness. I stumble into evidence here and there without even looking for it, including this Frida Kahlo blouse and jacket in a Venice store window, this Mexican restaurant in Venice and a painted sign for a Mexican restaurant in London. After 500 years, it's about time.

Oaxaca: the city of art

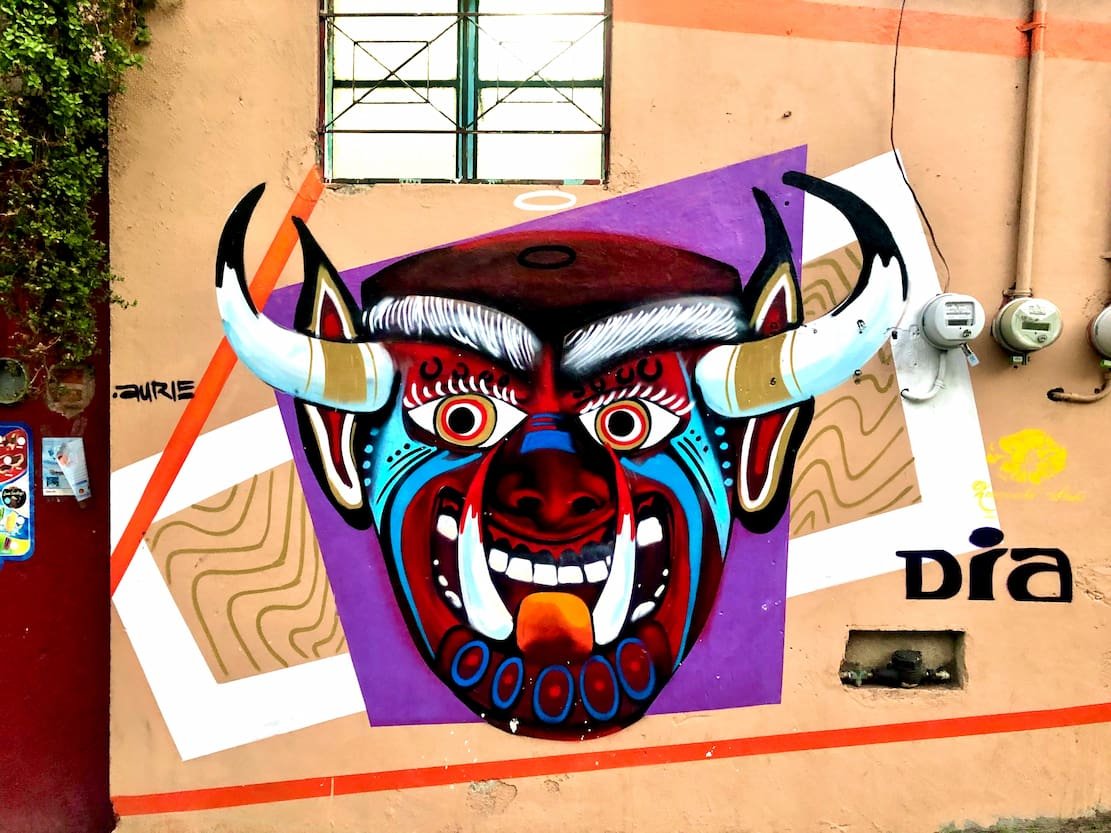

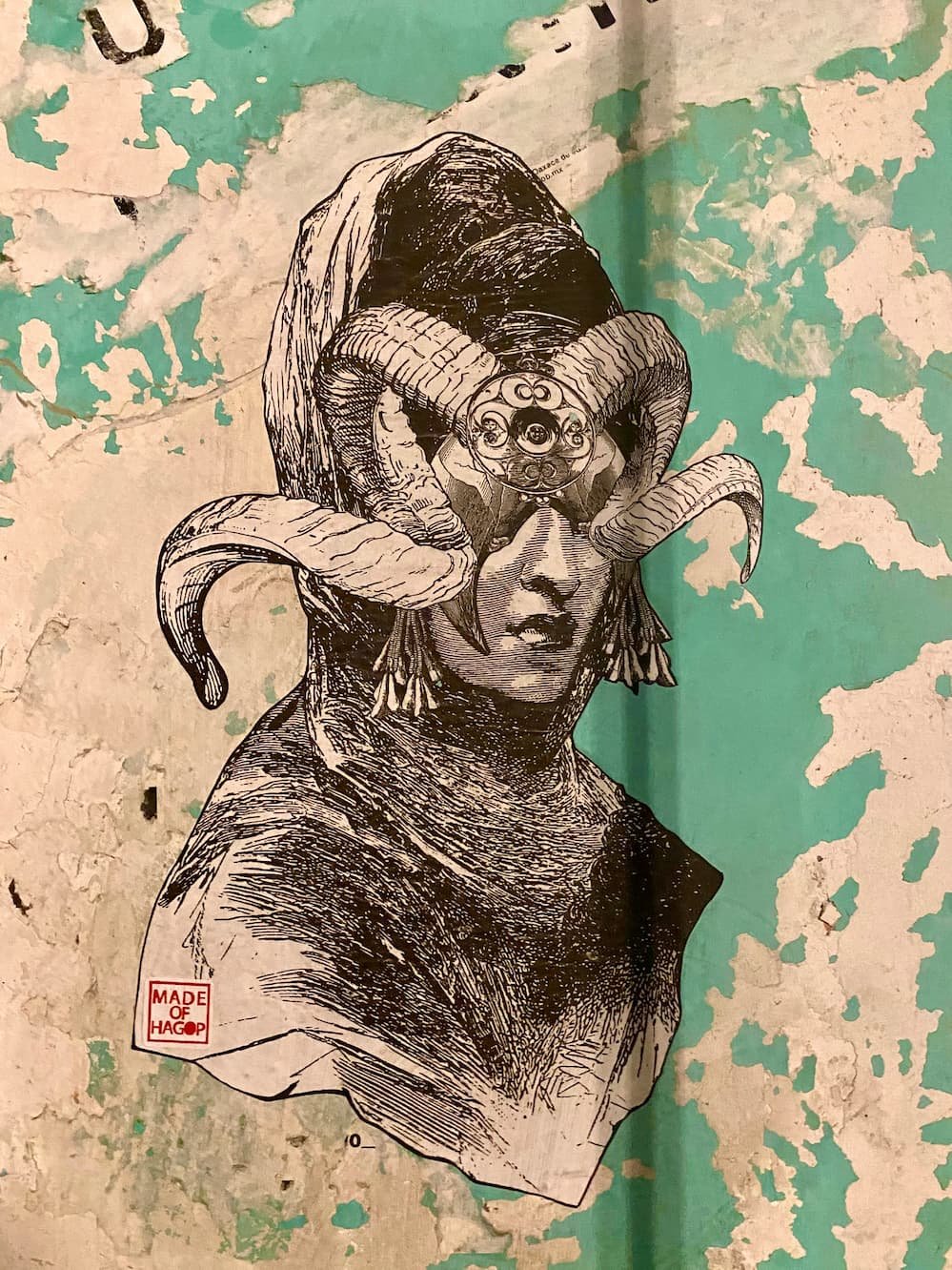

One of the many joys of living in Oaxaca is the city's dazzling, colorful street art. Just walking from our apartment to a restaurant down the street gives us an amazing look at more than 30 incredible works of art. And the total number in the city must be in the thousands.

Public art is everywhere in Oaxaca — on the streets in temporary installments, a near infinite variety of artistic crafts for sale in markets, stores and workshops all over the Oaxaca Valley and in the many art galleries in the city center.

The murals tell stories, register protest, recall history and bring indigenous religion and mythology to life.

Rebels, critics and insurgents who have spoken out or fought against repression are plainly memorialized. The iconography of pre-hispanic mythology is everywhere — skeletons and the content of the Aztec afterlife — hummingbirds and spirit guide dogs. And the beauty of indigenous clothing and traditions make up blazingly colorful murals all over the city. Some murals exist to decorate businesses like shops, restaurants and bars.

Every time we return to Oaxaca, dozens more have been painted. Because of all those incredible murals, Oaxaca is a fascinating place to just walk around.

In short, the murals reflect the thoughts, feelings, anxieties and fever-dreams of this amazing city.

We just added a new Oaxaca Mezcal Experience for this year!

Greetings from Oaxaca!

I’ve got some great news! By popular demand, we've added a new Oaxaca Mezcal Experience this year! It happens December 3-9.

We’ve been in Oaxaca enjoying our own personal “Gastronomad Experience” with our local friends. This place is magnificent and truly inspiring! I can’t wait to share this new Oaxaca Mezcal Experience with you!

There’s something truly magical about Oaxaca — its deep blue skies, puffy white clouds, colorful buildings, cobblestone streets, friendly people, delicious food and ever-present history. It fills your heart with joy and happiness.

And the food!! This isn’t the Mexican food that you already know and love. Oaxaca is its own gastronomic universe, with some of the world’s most delicious flavors and ingredients.

The Wall Street Journal called Oaxaca the “Mexican city every food-loving traveler should visit now.” And Travel + Leisure magazine named Oaxaca the Best City in the World to travel to for the last two years in a row!

And these publications are talking about mere tourism!

Imagine the unimaginable — skip right past the tourism and go directly into the heart of the real, authentic Oaxaca. We lovingly craft a bespoke itinerary full of fun and delicious surprises. Get to know our brilliant friends, some of whom are the city’s top chefs and food makers. Experience magical gatherings in breathtaking settings with the most exquisite foods and drinks this region has to offer.

This isn’t just travel. It’s time travel. It’s travel beyond the world that you know and into a world you never imagined.

And while we do enjoy some of Mexico’s greatest wines, we also deeply explore the Oaxacan tradition of mezcal. (Because of US import restrictions, most of Oaxaca’s best mezcal cannot legally be sold in the United States. You can find it only in Oaxaca.)

The Oaxacan Mezcal Experience is more than an experience. It’s a magic spell. And you’ll be enchanted completely.

But space is limited. Secure your spot today and prepare for a transformative culinary experience! Get pricing and book now!

Why Mexico City is the Center of the Chocolate World

Everybody loves chocolate. The intoxicating aroma of freshly roasted cacao. The decadence of a deep, dark chocolate dessert that melts in your mouth. The joy of hot chocolate.

When people associate the idea of chocolate with a place, they usually think of a European place — Switzerland, Belgium or Vienna, for example.

But Mexico City is by far the greatest city in the world for exploring chocolate — especially during our Mexico City Cocktail Experience. And here’s why.

Europe’s relationship with chocolate began in the 19th Century when, in 1828, Dutch chemist Conrad van Houten invented the cocoa press, separating cacao butter from the solids and, in doing so, invented cocoa powder. The commercial availability of cocoa powder enabled pastry chefs and home cooks alike to buy, store, cook and bake with chocolate far away from where it's grown or roasted.

Van Houten’s work also enabled the invention of chocolate bars by Joseph Fry in 1847, as well as chocolate candies.

Today, Europe produces a dizzying array of delicious chocolate foods and drinks —pralines, chocolate truffles, chocolate bonbons, chocolate cakes, mousses, custards, cookies, chocolate tarts, soufflés, milk-based hot chocolate, chocolate liqueurs like crème de cacao, chocolate covered nuts, chocolate spreads like Nutella, and, of course, chocolate bars.

Every kind of cocoa powder-based European treat is available in exquisite form in Mexico City as well, both in the most traditional European form, and also in a Mexican flavors-infused variation (like chocolate candies with chiles). The city’s restaurants, pastry chefs, bakeries and confectionaries make all the European chocolate foods, often matching European quality.

While Europe’s relationship with chocolate began 200 years ago, Mexico’s began 5,000 years ago. That’s when the Olmec civilization starting using and eventually domesticating the cacao bean in Southern Mexico, which was used by Olmecs and later Mayans, Aztecs and other Mexican civilizations as both an important beverage and a currency.

Our word “chocolate” is from the Aztec word “xocolātl” (pronounced something like show-ko-LA-tull), which means “bitter water.” Mesoamericans typically mixed chocolate with corn and spices (but no sweetener) and drank it.

Because chocolate has served as an important food in Mexico for millennia, regions, indigenous groups and even small villages have their own unique ways to prepare and consume chocolate.

Mexicans in various parts of the country enjoy ways to consume chocolate that few Europeans have ever even heard of, such as chocolate atole (made with corn and milk), chocolate tamales, chocolate-dipped chiles, chocolate-covered fruit and, of course, the ultimate use for chocolate — black mole. Mexicans also use species of cacao never used in European chocolate.

The most common way for Mexicans to consume chocolate, though, is water-based hot chocolate containing sugar, almonds and cinnamon mixed and frothed with a molinillo — (a mixing stick introduced by the Spanish).

Mexico City is also great with American chocolate ideas like chocolate beer and chocolate cocktails, chocolate chip cookies, brownies and chocolate muffins.

Markets throughout Mexico offer custom chocolate blending and grinding. While European cooks mainly use industrially produce cacao powder from cacao grown in Africa, Mexicans buy freshly roasted and ground-to-order chocolate with custom mixes of sugar, cinnamon and other ingredients from cacao grown in Mexico. The quality of Mexican chocolate is far higher than European chocolate, on average.

But Mexico City is the greatest city in the world for chocolate for one simple reason. It’s the only place on Earth with all styles of European chocolate, all styles of American chocolate and all styles of Mexican chocolate. (If there’s an obscure style of chocolate in some remote Mexican region, you can also find it somewhere in Mexico City.)

And while everything we do during the Mexico City Cocktail Experience is a secret surprise, it’s a safe guess that there may be chocolaty deliciousness involved. - Mike

You can taste Mexico City, Oaxaca and Baja in every great Mexican dinner

“Get dressed! We’re going to an oyster tasting,” Amira told me.

It was late afternoon in November of 2020. I was in our apartment in the city center of Oaxaca, Mexico, and had just settled down to work.

But this is Oaxaca. Resistance is futile. Great food events happen almost constantly, it seems. (The night before, Amira had been invited to a chef’s roundtable dinner with several of the city’s prominent chefs and food producers, plus a special guest chef from Japan. The night after, we would enjoy the anniversary of a restaurant called Oaxacalifornia.)

But tonight, an “oyster tasting” at Casa Oaxaca Hotel.

What all these events had in common was Chef Alejandro Ruiz, the Godfather of Oaxacan cuisine. He organized all three events, has run Casa Oaxaca Hotel and co-owns Oaxacalifornia (as well as several other fantastic restaurants in Oaxaca). In addition to organizing dozens of incredible food events in the city, Chef Alex also trains on, consults over and represents Oaxacan food to Mexico and the world. Over the years, he’s also become a close friend of ours (and a major ingredient in our Oaxaca Mezcal Experience).

We arrived at the “tasting” to discover that we were among only around eight or so people — a few local chefs, plus Amira and me. Leading the event was a guest: Mexico’s leading supplier of seafood to the country’s best restaurants, including Mexico City’s Pujol. His name is Ezequiel Hugo Hernandez Zúñiga. He brought oysters and PowerPoint.

Chef Alex’s staff served our tiny gathering wave after wave of oysters on the half-shell, each a different type and accompanied by all kinds of spicy and flavorful sauces, all the while Mr. Zúñiga delivered a master class on the world of oysters. After the half-shell oysters, we were treated to incredible oyster soups and tacos.

All the while, we drank paired wines, beers and cocktails, plus mezcal, of course.

The lecture lasted three hours. The dining around six hours. But the conversation continued late into the night — all about oysters, food, restaurants and cooking.

At some point, probably around 1am, the kitchen staff (which had been standing by the whole time) figured we must be getting hungry again, and started bringing out tlayudas (a kind of giant Oaxacan tostada folded in half and eaten like a sandwich) and other Oaxacan comfort foods.

I told Chef Alex that I really enjoyed the mezcal we had been drinking. “You want to try some really great mezcal?” I said “of course!” and he rang up (OK, woke up) a man named Chucho Espina — another serial food entrepreneur, restaurant owner and mezcal maker and mezcal expert.

And so around 2am, we followed Chucho to an art gallery to taste mezcal. So we sat in one of the gallery rooms surrounded by photography, with its gravel dirt floor, around a hastily assembled table, and tasted some of the most incredible mezcales I had ever tried until the sun came up. (Chucho has since also become a friend, and he always seems to show up at every Oaxacan gathering, and at his own bars and restaurants, offering surprising, amazing and unique mezcales.)

The evening (and night, and morning) was unforgettable, totally unique and quintessentially Oaxacan.

Over the years, I’ve noticed that almost every incredible high-end dinner in Mexico involves three locations: Mexico City, Oaxaca and Baja California. In fact, we had been exploring the Mexico City food scene for years before visiting Oaxaca for the first time, and noticed how enamored Mexico City chefs were about Oaxacan flavors, herbs and other ingredients. Oaxaca is considered the epicenter of Mexican mole, for example. And 80% of the world’s mezcal is produced in the state of Oaxaca.

Great Mexican fine dining almost always involves Mexico City chefs or culinary culture, Oaxacan flavors and ingredients and Baja seafood and wine (The main wine country of Mexico is Valle de Guadalupe near Ensenada).

Mexico City is one of the world’s greatest places for food, which is why we love our Mexico City Cocktail Experience. Mexico is the only country in the world with two restaurants currently in the Top Ten of the World's 50 Best Restaurants list — Pujol and Quintonil, both in Mexico City. And both these restaurants specialize in Oaxacan flavors, dishes and ingredients and Baja seafoods (supplied by Mr. Zúñiga) and wines.

Our “oyster tasting” was no different, bringing together Mexico City, Oaxaca and Baja for the ultimate Mexican food experience.

Of course, Mexico has 31 states and thousands of distinct food cities and areas, and it’s all delicious. But the secret sauce of high-end Mexican cuisine almost always bring together Mexico City, Oaxaca and Baja. -Mike

The Guelaguetza: Oaxaca’s epic indigenous cultural event of food, dance, music and spectacle

The Guelaguetza: Oaxaca’s epic indigenous cultural event of food, dance, music and spectacle

Each summer, the city of Oaxaca dresses up in retina-searing colors and transforms itself into the most important indigenous cultural event anywhere in the Americas.

We've had the privilege of attending this year's Guelaguetza Festival for the first time, thanks to the help and courtesy of Oaxacan friends. And we have loved every minute of it.

Oaxaca’s Guelaguetza is a big deal because Oaxacan culture is inseparable from indigenous culture. The event showcases the roots and traditions of the spectacularly diverse indigenous cultures in Oaxaca through dances in group-specific costumes, big parades, gatherings, musical events, artisanal crafts and indigenous-forward (pre-Hispanic) food festivals.

Although loosely based on pre-Spanish traditions, the modern Guelaguetza began in 1932 on the 400th anniversary of the founding of the City of Oaxaca by the Spanish empire.

Since 1969, the Guelaguetza has been celebrated on the two Mondays immediately following July 16 (except when that first Monday lands on the birthday of indigenous Oaxacan former president Benito Juárez, which is July 18.) But the informal, citywide festivities begin days before the official start and continue throughout the two weeks, ending today. It’s an endless, crowded, festive, happy party.

The word Guelaguetza is Zapotec for “reciprocal exchanges of gifts and services” or “offering.” (The Guelaguetza also integrates ceremonies around Our Lady of Mount Carmel, or “Virgen del Carmen.”)

Because this cultural exchange is so beautiful and delicious, the Guelaguetza has evolved into a performance spectacle and feast for everyone's eyes, which is a source of ongoing controversy in Oaxaca. Some indigenous leaders say the celebration is being commercialized and performed for outsiders, mainly visitors for elsewhere in Mexico. And that’s obviously true for some of the centrally planned activities in the City of Oaxaca, but not at all true in the many events that take place in the surrounding villages. Many of the different villages or municipalities hold their own local Guelaguetza celebrations.

The Guelaguetza is a fraught cultural event for Mexico. Commercial aspects infringe on the inherent traditions and meaning behind the rituals and the objective of cultural exchange. Despite the differences and controversies, the Guelaguetza has managed to amalgamate cultural and identity expressions in its idea of unity and coexistence between ethnic groups and the general population. As each ethnic group celebrates their specific identity as well as their ethnic differences, despite the inequities within the society at large, Guelaguetza fosters conviviality and convergence in a genuine community celebration that exalts coexistence between diversified lifestyles. On the whole, the event is all about love for indigenous Oaxaca, both by the locals and for visitors as well.

The Guelaguetza is significant for indigenous Oaxacans, as its diversity of language and culture make it important and meaningful to the survival of their cultures. Everyone comes together for this once-a-year super fiesta to share and celebrate the diverse world of Oaxacan indigenous communities where they can bond and connect with each other.

The Guelaguetza Festival brings together delegations that represent the eight regions of Oaxaca (Cañada, Costa, Istmo, Mixteca, Papaloapan, Sierra Sur, Sierra Norte y Valles Centrales.) Only 21 delegations represented the state's 590 municipalities this year. The participants are selected through a lottery system from the hundreds of groups and municipalities who are members of the different ethnic groups from different regions and who speak mutually unintelligible languages.

The language landscape reveals the cultural diversity in Oaxaca. More than one-third of all people in the State of Oaxaca speaks an indigenous language, and many do not speak any other language, including Spanish.

The largest group alone, called the Zapotecs, speaks more than 62 distinct and often mutually unintelligible languages. The Mixtecs speak dozens. There are 14 other distinct ethnicities in Oaxaca (in order of population: Mazateco, Chinanteco, Mixe, Chatino, Trique, Huave, Cuicateco, Zoque, Amuzgo, Oaxacan, Tacuate, Chochotec, Ixcateco and the Popoloco and these groups each have their own languages or language families.)

While the Guelaguetza draws visitors from all over Mexico, other countries and indigenous peoples from all over Southern Mexico, the main state-sponsored festival events (which happens on El Cerro del Fortín in a purpose-built, 11,000-seat facility called the Guelaguetza Auditorium) take place on the two consecutive Mondays towards the end of July. Less than 3,000 tickets were sold to the general public in 2022, which sold out in a matter of minutes. The few tickets sold online can only be purchased using a specific local credit card.

The remaining tickets are free to Oaxacans who wait in line overnight to get them. Generally, it's not easy for tourists and foreigners to attend the Guelaguetza. The ticket system is geared for ensuring that most, if not all, tickets available for purchase and for free go to local Oaxacans.

During the main Guelaguetza event performances, at the end of each dance, the dancers throw food into the audience, ranging from cookies and bread to candy and tamales. After the famous annual Flor de Piña dance, the performers actually throw whole pineapples into the crowd -- we caught one of them, took it home and ate it. We also caught all kinds of breads and cookies.

The Guelaguetza events involve music, singing, dancing and costumes. Dancers wear exquisite hand-made traditional outfits that span the range from totally Spanish to totally indigenous and everything in between. Additionally, there are other concerts and events that are separately scheduled as part of the festivities with big name Mexican artists including Lila Downs, Maná and Los Angeles Azules (all of which we attended!).

We were invited by a local Zapotec friend to a village with a population of 2000 Zapotecs. The celebrations included the dance performances, food festivals, fireworks, rituals at the local church and even their own version of bullfighting, which didn't involve any harm to the bulls, as no knives or swords were used.

We’ve always wanted to attend the Guelaguetza, and we feel so privileged to take part this year — which is a special one, as the event was canceled in 2020 and 2021 because of covid.

The existence of the Guelaguetza in Oaxaca turns the entire city into a massive cultural gathering and nearly state-wide fiesta that lasts for two weeks. Experiencing the profound jubilation and joy of Oaxacans, nationals and all visitors coming together has been unforgettable. Seeing all the delegations from the different municipalities from the various regions of the state share their cultural roots, traditions and customs has been transformative.

Why Oaxaca really is 'the best city in the world'

Travel & Leisure magazine polled its readers on the best cities in the world for travel, and they published their list of the world’s top 25 cities.

The list included some unsurprising locations, including Florence, Italy; Seville, Spain; Tokyo, Japan; and, of course Rome, Italy.

But beating them all to be ranked the #1 city in the entire world is the place where we are right now: Oaxaca, Mexico!

“Wait, what?!?” you might ask?

We run across people all the time who have never even heard of Oaxaca, and more still who don’t even know how to pronounce it. (It’s: wha-HOCK-a). How could a small Mexican city be “better” than Florence and Rome?

But for those of us who know Oaxaca best, the reaction was: “Oh, yeah — definitely!” (And we agree, which is why we host our epic Oaxaca Mezcal Experience here!)

Travel & Leisure says Oaxaca is best because of its “vibrant culture, beautiful weather, a landscape that spans from soaring peaks to cerulean surf, and some of the country's most iconic architecture.” (The city of Oaxaca has no “surf” — it’s a six-hour drive to the coast.) They also mention the incredible climate, “world class cuisine,” the local markets, and proximity to Monte Albán, the spectacular ruin of the ancient Zapotec imperial capital.

They go into some minor detail about the wonders of mezcal, most of which is produced in the state of Oaxaca within a short drive from the city.

The article didn’t mention that both mole and mezcal are specifically Oaxacan, rather than generally Mexican, cultural gifts and that Oaxaca boasts a wide range of ingredients mostly unique to the state, such as Oaxacan cheese known as “quesillo” and herbs like hoja santa, or tlayudas and many others local delicacies.

But they missed the Big Story about Oaxaca.

Since the beginning of the Spanish conquest and occupation of Mexico, the Spanish and their descendants in the New World have tried to forcibly “civilize” the “natives” with European food — bread instead of tortillas, wheat instead of corn, wine instead of pulque, sandwiches instead of tacos.

Fancy white Mexicans stigmatized indigenous foods for centuries as the stuff of poor, unsophisticated “Indians,” clinging to European foods and identifying with American gringo food culture more than the foods of indigenous peoples of Mexico.

But the suppression of indigenous food culture was less successful here in the South of Mexico.

In the same way that America gets more Mexican the closer you get to the border (Southern California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas have vastly more and better Mexican food than Maine, Connecticut and Vermont, for example), Mexico is the reverse — the closer you get to the US border the more American and Americanized the food gets.

As one small example, flour tortillas (wheat was unknown to the Americas before the Spanish brought it here) probably originated in present-day California when it was part of a neglected Spanish territory called Alta California, and were first mass-produced in Los Angeles, California. Four tortillas are, essentially, American tortillas. In fact, Mexican menus call tacos made with flour tortillas “gringas” — which essentially means “American tacos.”

Today, flour tortillas are more commonly eaten than corn tortillas in the Northernmost Mexican states of Chihuahua, Durango, Sonora and Sinaloa and practically non-existent in the Southernmost states of Oaxaca and Chiapas.

The further South you go in Mexico the more cultural memory exists about the cultivation, preparation and consumption of indigenous foods. In fact, more than half of all the people in Mexico who speak indigenous languages are Oaxacan, with one-third of the state’s population speaking languages other than Spanish and half that number unable to speak Spanish at all.

Zapotec is the largest indigenous language family in Oaxaca, and within that family are some 60 distinct languages. Mixtec is the other major language group here. And the state of Oaxaca includes a vast range of distinct ethnic groups, including the Triques, Amuzgos, Cuicatecs, Chocho, Popoloca, Ixcatec, Zoque, Mixe, Chontalees, Chinantecs, Huaves and even the Nahua (descendants of the Northern Aztecs).

Many of these ethnic groups, including and especially the Zapotec, say they were never conquered by the Spanish. And in fact that’s true — the relationship between the Spanish empire and the Oaxacan indigenous peoples was a negotiated settlement of mutual non-interference (with a few historic spikes of violent opposition and oppression). Indigenous Oaxacans maintained their pre-Hispanic culture far more than other groups in Mexico.

The Mexican elite suppression of native Mexican foods was put increasingly under pressure in the late 20th and early 21st Centuries, as its popularity grew throughout European Mexico, the United States and, eventually, Europe and the rest of the world. Of course, native ingredients and foods never went out of general popularity in Mexico. But it was always considered the food of poor working stiffs, not refined foodies.

But in the last 20 years, that has changed, with Mexican chefs trained abroad starting to re-embrace indigenous foods and ingredients, culminating in the designation of Mexico City’s Pujol restaurant as the very best restaurant in all of North America and the #5 restaurant in the entire world according to the World's 50 Best Restaurants list. Pujol is famous for its focus on indigenous ingredients — mole is featured heavily, and guests are served sauces made with ant eggs, for example.

There isn’t a single French restaurant in the top ten, but there are two Mexican restaurants in the top ten, both featuring indigenous ingredients.

The world fell absolutely in love with indigenous Mexican food, and so have Mexico’s elites. As a result, there has been a kind of gold rush among Mexico City chefs to come to Oaxaca and learn from indigenous Oaxacans or what locals call "traditional cocineras."

We've been exploring Mexico City and Oaxaca for many years and discovered their culinary prowess and remarkable culinary traditions long ago, which is the reason we host The Mexico City Cocktail Experience and The Oaxaca Mezcal Experience with the top chefs and artisans of the regions.

We've witnessed how Oaxaca has become acknowledged globally for its culinary traditions.

Oaxaca is alive and buzzing with culinary excitement. It’s the center of a Mexican food renaissance. Chefs and food producers and mezcal makers are energized in a frenzy of learning, exploration and exposition. This is expressed in the form of tastings, collaborative dinners and mezcal-fueled, food-centric parties.

For the food obsessed (including us), Oaxaca is the most exciting place on earth right now. And it’s why Oaxaca is, in fact, the best city in the world. And why Oaxaca became our favorite place long ago.

Magic Oaxaca!

The magic of gathering around the table with kindred spirits is unforgettable. It’s the place where lifetime memories and lifelong friendships are created.

We had the pleasure of creating a magical gathering with an exquisite meal prepared by our friend and talented chef Israel Loyola Espinosa at the beautiful Hotel Sin Nombre during the recent Oaxaca Experience. But there are always secret new gatherings and endless surprises during this once-in-a-lifetime Oaxaca Experience. We can’t wait for you to feel the magic of gathering for The Oaxaca Experience in December.

On the places you won't find in the travel guides

When you’re on a two-week vacation, you need to turn to the travels guides — books, sites, apps, blog posts, social media posts and maps recommendations. But when you’re living abroad as a digital nomad, you have the time to explore, find the stuff that’s not in the guides and try them out.

In this picture, I’m in line for a dive Xochimilco pulqueria (I’m the gringo at the back of the line with the giant backpack). This bar is purely local. And, in fact, it’s unlikely to spot gringos even in the neighborhood.

We love this kind of discovery. And the reason is that once any bar, restaurant or other thing blows up in the travel guide, it changes. It’s great to experience the unchanged places, which authentically cater to locals.

The only way to discover local-only establishments at scale is to spend months and months in a place, wandering around and relying on serendipity.

Inside the Magical World of Mezcal

Do you know what mezcal tastes like?

Mezcal is a distilled beverage made from cooked and fermented agave juice. But that definition barely scratches the surface of this incredibly complex spirit.

Most people outside Mexico are more familiar with tequila, which is in fact one kind of mezcal. All tequila is made from agave tequilana Weber, or Weber blue agave and cooked in steam ovens, usually in the state of Jalisco.

Mezcal, on the other hand, can be made from any of roughly 50 species of agave, and each brings a different taste to the final product.

Mezcal agave species have names like Tobalá, Americana, Durangensis and many others.

One of our favorite species is Agave Karwinskii, which is grown mainly in Oaxaca, and which comes in varieties called Cuishe, Baicuishe, Madre Cuishe, Barril, Tobaziche and Verde, each variety offering differences in taste (but all very good).

One way to look at the difference between tequila and mezcal is that tequila is simple and mezcal is complex. Tequila is relatively simple, because it's made with one agave type and one production method. Mezcal is complex because it's made from many agave types, many production methods, many variations on flavors and (like tequila) also has variety introduced through aging.

The word mezcal is a bastardization of the Nahuatl word "mexcalli," which means "baked agave."

Mezcal is made in the Mexican states of Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Zacatecas, Michoacán, and Puebla. But most mezcal is made in the state of Oaxaca.

Artisanal and traditional mezcal making is very much a phenomenon of Oaxaca. Of Mexico's 625 mezcal production facilities, 570 of them are in Oaxaca, producing 90% of the country's mezcal.

How Mezcal is brought to life

Mezcal is made from agave at the end of the plant's life.

Most agave plants are harvested after roughly 10 years, although some can grow for 30 years before harvesting, depending on the agave species. Most mezcals are made with farmed agave. But some are made with wild agave, and these have distinct flavor differences from their domesticated cousins.

When most agave species ripen, they bloom by quickly growing a single flower stalk up to 15 feet high, a process that, if allowed to occur, enables the plant to seed before dying, but the flowering spoils the piña for agave making. Mezcal growers chop this stalk off to preserve the piña until they can harvest it.

They chop the spikey leaves off with a machete, then hack and shovel the "piña" at the base to remove it from the roots. This piña is sometimes roundish, sometimes elongated, depending on the variety of agave.

The piñas are cooked for a few days, often in underground pits. Underground baking causes the smokey taste in most mezcals. They can also be cooked with steam ovens in the same way tequila is cooked.

The cooked piñas are then mashed, sometimes with a stone wheel pulled by a horse, and then fermented with water in wood barrels or vats.

The fermented liquid is then distilled, usually twice — sometimes thrice — in copper or clay pots. (Ancestral distillation happens in clay pots and wood pipes.)

After distillation

The reason mezcal is available in such breathtaking variety is that so many factors contribute to the taste: The species of agave, the cooking method, the fermentation time, the distillation process, the aging process, and also things added to affect the flavor. These can include fruits, herbs, spices, chicken, turkey or duck.

Mezcal flavored with poultry happens either during steam cooking or distillation. In other words, the turkey is not introduced to the mezcal after distillation. Produce, if used for flavor, is added to the boiling mescal during distillation.

For some types, a moth larva is added during the bottling process for flavor.

Most mezcal is not flavored.

Like tequila, mezcal is categorized by the degree of aging — Joven, Reposado, and Añejo.

Some of the smoothest and most flavorful mezcals are aged in wood barrels, and these tend to be yellow-orange in color.

When mezcal is aged in glass for at least a year, it's called Madurado en Vidrio.

The global mezcal craze

Abroad, mezcal is increasingly used in trendy craft cocktails, such as the "Oaxaca Old Fashioned." And, of course, mezcal is a celebrated foundation in Mexico City of the ongoing fusion of ancient mexican culinary traditions with modern and international ones.

Mezcal is growing fast in popularity outside Mexico, especially in the United States and Japan. One reason is that, in past decades, Mexico shipped mainly only low-quality mezcal abroad and the world didn't know how amazing good mezcal is. But in recent years, gringos have discovered the good stuff, and now can't get enough of it.

In 2019, the United States surpassed even Mexico in mezcal consumption, gobbling up 71% of all mezcal exports. In the US, however, mezcal consumption is stilled dwarfed by tequila, which is still much more popular.

Mezcal: a fundamental part of Oaxacan culture

In Mexico, mezcal is normally drunk straight and sipped slowly (never as a "shot," as is common in the United States for tequila). Mexicans say you "kiss" the mezcal, meaning that you take in each sip what amounts to only drops at a time — it enters the mouth practically as a vapor.

For the drinker, mezcal is more like wine than other spirits. Terroir, the agave variety and the mezcal maker and his methods determine the outcome, which can be variable in the extreme. Different mezcal types can hit your mouth like liquid fire or can be mild as water. It can offer up notes of herbs, cinnamon, sage, peaches or caramel. It can be smokey or fruity. Bitter or smooth.

In Oaxaca, mezcal is taken for every social occasion, from weddings to the most casual visit by neighbors. It's a central part of Day of the Dead, where the deceased is poured a glass of mezcal, which is placed on the home altar often in front of a framed picture of the deceased, and then loved ones sit and drink their own.

Once you've spent time in Oaxaca, the taste of mezcal becomes inseparable in the mind from the "vibe" of Oaxaca, especially the surrounding countryside and the Oaxaca Valley, where much of the agave is grown.

What does mezcal taste like? It tastes like Oaxaca.

Tortilla magic

We had a lovely outdoor breakfast on the rooftop of a place that makes great tortillas. That flat tortilla on the plate in the upper right of the picture above is actually an egg cooked inside a tortilla. So good.

Oaxacan cheese with a little something extra: chilis

Another treat from the Tlacolula market here in Oaxaca, Mexico: cheese made with chilis. You would think this would be super spicy, but the chilis are all very mild and the cheese is mild, too. It’s got very subtle flavors. The indigenous market sellers use banana leaves as the “packaging.” So delicious.

Amira picked up some turkey eggs at the market

These two turkey eggs Amira bought at the Tlacolula market here in Oaxaca, Mexico, are just plain big. We’re going to make omelets with them later.

Anatomy of the perfect tamal

These were the most delicious, authentic and, well, perfect tamales we have ever tried. Heirloom corn masa, super flavorful locally grown beans and — the pièce de résistance — wrapped in the herb hoja santa, then corn husks. The salsa is handmade, medium hot from some relatively obscure chilis, smokey and wonderful.

Hoja santa, which is amazing when well used but not so great when cooks and chefs don’t know how to use it, is native to this region (Oaxaca, Mexico) and used by the Aztecs as medicine and even in chocolate.

The corn to beans ratio is also perfect. Nearly all modern tamales are overstuffed with too much cheap GMO corn. This is how they used to be made, with far less higher quality corn.

Note that all these ingredients are prehispanic and local — no cheese, chicken or other imported ingredients.

This stuff has ruined me for hot sauce

First things first: When we arrive in Oaxaca, we grab a jar of this stuff. Macha is oil made spicy with pepper flakes. It also contains peanuts for flavor. It’s very hot and very tasty.

Of course, Amira makes a much better chili oil, loaded with garlic as well. But this will hold us over until she can get to the local markets to buy the stuff she needs. -Mike

Traveling to Oaxaca to explore the food, culture and architecture of this Mexican gem

Waking up in Oaxaca to the chirping of birds and the hum of this city on the second day of spring was nothing short of glorious. Even after arriving exhausted from California, being in Oaxaca again is a dream come true. We had been scrambling to get ourselves ready to reclaim our digital nomad lifestyle after sheltering in place for many months. (Note: This post is an excerpt from the Gastronomad Newsletter.)

We’re living in a traditional Oaxacan house, which belongs to a friend of a friend. It’s as pleasant as can be and perfect for doing the work Mike and I do. It has a nice big kitchen with lots of natural light where I can work on creating recipes for the Spartan Diet Journal.

The house has a wonderful open air courtyard where hummingbirds love to visit and we enjoy watching them from floor-to-ceiling windows as we sit in front of our laptops every day. We have a nice hipster bakery cafe next door — the smell of baking butter is wafting through the windows as I write this.

Travel is even more meaningful than it used to be somehow. Mike and I have truly loved our lifestyle and always feel so grateful and blessed. But traveling and seeing our Oaxacan friends again makes us so happy (even if we can't hug and we have to meet outdoors keeping distance and wearing face masks).

Pandemic woes are temporary. But Oaxaca is eternal.

Oaxaca is a state. But the history and culture (including food culture) of Oaxaca centers on the Oaxaca Valley in the Sierra Madre Del Sur Mountains.

The Zapotec civilization ruled the Oaxaca valley between around 700 BC until two years after the first Spanish set foot on the Mexican mainland (around 1521). Although there are many indigenous languages spoken in the State of Oaxaca today, the main language group is Zapoteco, which has 7 distinct languages and more than 100 dialects. It's mainly these Zapotec peoples — their farming and food practices — that make Oaxaca such a unique culinary paradise.

Mexico is the food capital of the Americas, and Oaxaca is the food capital of Mexico.

The Spanish brought the food cultures of the Arab world (having previously expelled the Moors from Spain, but not their food culture) and Asia (having established a trade route between their various colonies, including in the Philippines and elsewhere in Southeast Asia). But no import could rival the incredible food types of the native Americans in general, and Southern Mexico in particular. This tiny tropical area, from the Oaxaca valley to Guatemala, and from the Pacific to the Atlantic, gave the world the cultivated or domesticated varieties of corn, chocolate, tomatoes, tomatillos, avocados, chilis, squashes, turkey, papayas, vanilla, jicama, chia seeds, allspice, many species of beans and hundreds of spices and herbs.

What's different about Oaxaca compared with many other Mexican regions is the combination of specific types of food production, plus the existence of 16 officially recognized indigenous groups faithfully preserving ancient foods and food practices.

While all of Mexico's "greatest hits" are present here — (amazing hot chocolate, corn tortillas, sweet breads, sweetened watery drinks and all the rest — Oaxaca is especially well known throughout Mexico for many traditional dishes and drinks originating in the region. Some of the more well known include:

mole

Oaxaca is called the "Land of the Seven Moles" because each of seven regions in the area is said to specialize in a specific type of mole that's different from the other six. These general mole types are black, red, light red, chichilo, green, yellow and manchamanteles (stainer of tablecloths). In fact, the "seven moles" label is an oversimplification or even a marketing fabrication. Despite this categorization, moles do vary widely from household to household and from seller to seller. Both the variety and quality of moles to be found in Oaxaca is overwhelming. (Mole is simultaneously the most Mexican and the most international food ever created, typically containing ingredients originating in the Americas (North and South), Europe, Asia and Africa.)

tlayudas

A tlayuda is a large (about the size of a medium pizza) thin tortilla roasted on a comal or over fire and topped with beans and a combination of other ingredients including lard, avocado, some kind of meat, Oaxacan cheese and salsa.

quesillo

Also known as Oaxacan cheese, quesillo is like a slightly more flavorful mozzarella or string cheese. Dominican friars brought the mozzarella idea from Italy to Oaxaca and used cow’s milk instead of buffalo milk. It's made into long ribbons and then bound up like a ball of yarn via the pasta filata process. While clearly an Italian import, the centrality of quesillo to Oaxacan dishes and also the quality of the cheese from Oaxaca makes it central to this region.

Oaxacan tamales

While tamales are universal to Mexico, every region has its different varieties. Oaxacan tamales are wrapped in banana leaves (as is common throughout tropical Mexico and Central America, and often contain uniquely Oaxacan moles).

tetelas

Tetelas are made with corn masa wrapped around a filling that can include beans, chilis, pork, mushrooms, cheese and other ingredients, folded into a triangle shape, grilled and then topped with sour cream, cheese and even roasted grasshoppers.

memelas

Memelas are thick corn tortillas shaped to be filled with a spread of refried beans, lard, quesillo and topped salsa (similar to sopes). They’re shaped like tiny pizzas with a little border around to keep the filling inside the open face memela.

chapulines

Also found throughout Mexico, chapulines (roasted grasshoppers) are especially associated with Oaxaca because of the quantity and variety available in the Oaxaca Valley. Local markets feature baskets of different types piled high and sold by the kilo. They can be eaten in or on various foods, or just eaten by themselves by the handful with chili, lime, garlic or onion and salt.

mezcal

One of the world's most exquisite, complex and sophisticated distilled alcohol drinks, mezcal is made from the agave plant (maguey). Before mezcal can be made, a mezcalero has to wait at least 7 to 9 years to begin the harvest and distillation process as most agave plants take at least 7 years to reach maturity at which point they can be harvested. Some wild agave species take 30 years to reach maturity. While mezcal is made in various regions around Mexico (including tequila, which is just one of the many varieties of mezcal), the vast majority is produced in the Oaxaca valley, which features vast agave plantations like the California wine country features vines. To make most mezcal types, the spikey leaves are cut off and the center "pineapple" is chopped, cooked underground, mashed, fermented and distilled using traditional handcrafted methods that go back generations. Different mezcales have different characteristics based on the type and age of the plant, the terroir of where it's grown, the harvesting, cooking, fermentation and distillation processes, the ingredients added for flavor (including in rare cases turkey meat or specific worms), the style and amount of aging and other factors.

pulque

Pulque, which is fermented agave juice, is to mezcal what beer is to whiskey — it's the same basic ingredient fermented rather than distilled. Before the Spanish arrived, pulque was a drink mainly for the upper classes of native societies, and also used ritualistically. Before the 20th Century, it was drunk more commonly than beer. Pulque is a delightfully sweet and sour drink by itself, and also flavored with fruit juices and other flavorings. In our experience, Oaxaca has the best-tasting pulque we've encountered in Mexico thus far.

The cultural expression of Oaxaca is apparent not only in its gastronomy, but also architecture, art, and preservation of its indigenous traditions that reward the senses with flavors, colors, aromas and beauty.

We're here mainly to continue preparing for the upcoming 2021 Oaxaca Experiences, which will bring people together from abroad to introduce them to local friends and the local community, as well as the beauty and deliciously unparalleled splendor of Oaxacan culture.

This will be a once-in-a-lifetime culinary and cultural immersion to experience Oaxaca’s authentic expressions of flavors, aromas and colors through a deep exploration of its food, beverages, architecture, folk art and handmade crafts as well as the warmth and wisdom of its people. We hope you get to enjoy this epic travel adventure. -Amira

The wonderful world of horchata

Note: This is an excerpt from the free Gastronomad email newsletter. Click here to subscribe.

Everywhere you go in Mexico, you can find wonderful beverages called aguas frescas — water-based refreshments. And these typically have some natural flavor, plus sugar. So you can find hibiscus, tamarind, pineapple, cantaloupe, guava, passion fruit, watermelon and dozens of others.

We have them in the United States, too. Just about every restaurant or street vendor in the US will offer at the very least lemonade or iced tea, both of which are "aguas frescas" — natural flavor, sugar and water.

One of the most interesting agua fresca is horchata, which is widely available in Mexican restaurants and taco stands in the United States. I suspect that most Americans and probably most Mexicans think horchata is from Mexico. In fact, the Americas are merely the final destination for a beverage that goes back thousands of years.

Americans got horchata from Mexico. Mexico got it from Spain. Spain got it from Valencia. (Valencia was independent from Spain when Spain conquered Mexico.) Valencia got it from North African Muslims (the "Moors"). The “Moors” got it from Egypt. The Egyptians got it from sub-Saharan Africans in what is now Nigeria and Mali.

They've been drinking horchata in that part of Africa since at least 2,400 B.C -- and they still drink it there. They call it kunnu aya.

The truth is that horchata has a long history, and every culture that embrace it made it their own.

Horchata began as a drink made from an African weed called cyperus esculentusk by the scientists, and colloquially as chufa sedge, chufa nut, nut grass, yellow nutsedge, tiger nut sedge, tiger nut, edible galingale, water grass or earth almond.

The weed also grew in the Americas. Plants in the tiger nut family were used as a food source by Native Americans, Africans and others at least 9,000 years ago.

(Our word "horchata" comes from the Valencian word "orxata." Because of New World bastardizations and novel ingredients, the Valencians now call it "horchata de chufa" to differentiate the newer innovations.)

Everybody changed it. The Africans and egyptians drank their tiger nut drink straight. The Moors or Valencians probably added sugar and cinnamon. The Spanish in the New World swapped the tiger nut for local substitutions.

Mexicans have always made horchata with rice. Central Americans use a roasted seed called morro. Various countries like Puerto Rico and Venezuela added sesame seeds. Ecuador makes pink horchata using flowers and herbs.

Both Mexicans and Americans started adding milk and other ingredients and flavorings. You can find crazy innovation and mashups around horchata in trendy restaurants in the US and Mexico. Now you can get horchata coffee drinks at Starbucks, horchata cocktails at bars and restaurants and find other variations on the horchata theme.

Regardless of nomenclature, horchata's journey is just like any other food's journey, traveling across geography, time and culture and evolving as it goes.

We have lived extensively in three of the major horchata-obsessed places — Valencia, Mexico and El Salvador — our favorite by far is Salvadoran horchata made with morro, which is flavored with cinnamon, nutmeg, coriander seeds and allspice. Horchata there is sweet, but that sweetness is balanced by a nutty roasted flavor that's amazing.

The place most obsessed with horchata is Valencia, which lack's Mexico's incredible diversity of drinks, but which does use tiger nut to make it. Valencia is Europe's only major producer of tiger nut, and they cultivate their own variety that doesn't exist outside of Valencia.

But we also love Mexico City’s best rice-based horchata during our Mexico City Experience (pictured) and enjoy very good Horchata during our Oaxaca Experience.

Horchata is a wonderful drink no matter where you enjoy it. But enjoying the local varieties in the places where they make it is a true joy.

Our Day of the Dead in a tiny village in Oaxaca

Amira and I were invited by our friend Dalia to her indigenous, Zapotec-speaking village in the middle of Oaxaca to join her traditional Day of the Dead celebration. Dalia is an amazing cook who grows all her own food and makes everything from scratch. Here are some of the highlights of our day.

Dalia made for us a regional specialty called atole con chocolate, which is a white corn drink very common throughout Mexico, but with a local twist: white-chocolate foam. She ferments a white variety of cacao under ground for three months, adds a little wheat, then grinds, sifts and froths it using a wooden Aztec hand mixing stick. This is the chocolate foam before being added to the atole.

Here’s the completed drink. It’s truly delicious and wonderful.

Dalia’s barbacoa is made from lamb from her own flock.

They make giant, very thin and crispy tortillas around here made from their own corn that they grow and usually mill by hand using an Aztec stone grinder called a metate. Amira got involved. Amira is wearing a kind of apron vest called a mandil, which they loaned her as a way for her to be part of the group.

This is the wood fired comal Dalia uses in the corner of her kitchen.

Dalia’s barbacoa is mind-blowingly good.

Here’s Amira enhancing the barbacoa in the traditional way with lime, cabbage with cilantro and green salsa all from Dalia’s garden.

Dalia’s mole negro, made very traditionally with more than 30 ingredients, is one of the best I’ve ever tasted.

After lunch we spent some time with Dalia’s ofrenda.

Dalia lit the candles.

Masks off for a moment so that Dalia could ritually purify Amira with copal, a flower they gather in the mountains and turn into incense.

We had a nice long walk through the village to Dalia’s mother’s house.

The ofrenda at her mother’s house is dedicated to her father, who passed away five years ago.

Dalia offered us some mezcal from a plastic jug. They buy it from a place that dispenses it from a barrel.

The multitalented Dalia also weaves. She makes rugs, table runners and more, all stunning.

She showed us how it’s done.

These are her naturally-dyed wool yarns, which she dies by hand using plants either picks wild in the mountains or grows in her garden.

These are tiny coasters!

Before leaving, we enjoyed these baked apples. Dalia just tosses them on the coals (in Spanish: Al rescoldo), then peels and slices them. We drizzled them with wild honey. The perfect ending to a very sweet visit.

Taking chips and salsa to the next level

Everybody loves chips and salsa. On our Gastronomad Mexico City Experience, we turn it up to 11, enjoying heirloom corn tortilla chips and salsas made with the rarest varieties of chili peppers. (These are grown only in Oaxaca and are used by only two or three exclusive restaurants in the city.)

A Gastronomad truism: Food always tastes best in the land where it originates. It’s about tasting the terroir of food, and also learning from the people that grow and make food with so much passion that your taste palate is forever transformed with every bite.

Join us in Mexico in 2021 for the Mexico City Experience or the Oaxaca Experience! Get ready to have your mind blown and palate thrilled by these delicious culinary adventures of a lifetime!

The joy of making (and eating!) Mexican mole

We love mole. Especially after what we experienced on Sunday, thanks to our friend (and Mexico's chile expert, Fernando).

Wait, mole? What's the deal with mole?

Most people think of mole as profoundly and exclusively Mexican. And, of course, that's true. But it's also probably the most international foods ever created. In fact, no food represents the Columbian Exchange more than mole.

Mole is a product of Spanish colonialism. The exact origins of mole are unknown. But we do know that recipes first emerged in the early 19th Century. And the moles you find today all over Mexico contain ingredients from Mexico, Europe, Africa and Asia. The states of Puebla and Oaxaca are most closely identified with a next-level culture of mole.

Inside Mexico, the regional variations and family recipes add up to probably tens of thousands of individual varieties. The variety of moles is endless. But what they have in common is two core Mexican ingredients -- chiles and chocolate. Beyond those ingredients, most moles contain between 20 and 40 ingredients, with some containing more than 100 ingredients. These include nuts, dried fruit, seeds, cilantro, seedless grapes, plantains, garlic, onions, cinnamon, black pepper, achiote, guaje, cumin, cloves, anise, tomatoes, tomatillos, garlic, herbs and more. Some moles even contain finished foods, such as tortillas or cookies.

(Outside Mexico, you're likely to encounter a bland, one-dimensional version of mole poblano.)

Mole is usually used as a sauce for meat or tomales, and also a marinade. At Mexico City's famous Pujol restaurant, mole is served as a course -- they bring you a plate with mole on it, which you eat with a tortilla.

Because of the wide variety of moles easily available at markets, and because of the internationalization and industrialization of Mexico's food culture, the art of making mole is being lost.

That's why Fernando and his family decided to stop this loss of culture, and learn how to make mole by making mole. Once they master the art of traditional mole making, they plan to teach others how to do it.

(Fernando's family owns a market called La Flor de Jamaica. And Fernando teaches our Gastronomad Experience guests all about chiles and salsa. He's also dedicated his life's work to preserving the knowledge, culture and botanical diversity of chiles and other Mexican food plants. That's Fernando pictured below wearing the giant hat.)

On Sunday, Fernando and his family (and we) all got together to make mole and other delicious foods completely from scratch using traditional methods over wood fires. This process of experiential learning was lorded over by an older woman who had learn from her mother and grandmother, and also a professional cook.

Most of the mole ingredients were toasted over a wood fire on a comal, then ground with a large flat volcanic-rock grinding stone called a metate and a hand-held stone called a metlapil.

This turned out to be a wonderful, slow, relaxing way to spend a beautiful Sunday in a small town in the state of Mexico, just South of Mexico City.

We basically ate all day, took turns grinding mole ingredients, hung out, chatted and ended up having a mind-blowingly fantastic mole chicken dinner.

We are so lucky to have a friend like Fernando, who generously invited us to participate in this day with his wonderful family. And Mexico is lucky to have a man like Fernando working so hard to preserve the nation’s unparalleled gastronomic culture.